In the fall of 2023, Unistellar observers joined forces with the Association Française d’Astronomie (AFA) to take another close look at a familiar visitor: Comet 103P/Hartley 2. This tiny but famously hyperactive comet has been the subject of several major observing campaigns over the past three decades, including a 2010 flyby by NASA’s EPOXI mission that revealed a peanut shaped nucleus spewing jets of gas from different regions.

Even though Hartley 2 was discovered in 1986, by astronomer Malcom Hartley at the Siding Springs Observatory in Australia, we are learning more about it to this day! Now, thanks to months of monitoring by the Unistellar and AFA communities during 2023, scientists at the SETI Institute and AFA have published a new scientific paper, led by Dr. Ariel Graykowski, that reveals Hartley 2 changing in a dramatic way.

Figure 1A from Graykowski et al. 2025: A “stacked image” made of 20 raw frames from a Unistellar telescope’s observation. The diffuse coma amongst the crowded background of stars is noticeable in the center.

A Small, Mighty, and Hyperactive Comet

Hartley 2 belongs to the Jupiter-family comets, completing one trip around the Sun every ~6.5 years. Though it’s only about 1.5 km wide — much smaller than the typical 5–10 km size of most comets — it long puzzled astronomers with how active it appeared.

In 2010, EPOXI discovered the source of this comet’s activity: carbon-dioxide jets blast from one end of the nucleus, while water vapor primarily escapes from the other. And unlike most comets, some of Hartley 2’s activity comes from tiny icy grains that continue releasing gas even after they leave the surface. This made it “hyperactive,” producing more gas than its small surface area should allow.

Because of these unusual properties, Hartley 2 has been observed extensively during previous returns in 1991, 1997/98, 2010/11, and 2017, each known as an apparition. But the 2023 apparition posed new challenges — its coma was broad and diffuse, and it sat against a very crowded star field. That made high-quality observations difficult to obtain, and it’s exactly why the participation of so many citizen astronomers was crucial.

Figure 2 from Graykowski et al. 2025: The lightcuve of comet Hartley 2 from the 2023 apparition. Data from the Comet Observation Database (COBS) is also shown. The data is fit to Unistellar and AFA data only, showing how the comet’s brightness changes as it approached and departed the Sun and Earth.

From 1986 to 2023

From early fall 2023 to winter 2024, Unistellar and AFA observers collected nearly 6 months of photometric measurements of Hartley 2, which measure the comet’s brightness. Despite the crowded background, these coordinated observations allowed scientists to build a detailed lightcurve — a record of how the comet’s brightness evolved over time.

By comparing the 2023 lightcurve with those from previous apparitions, researchers were able to track how Hartley 2’s activity has changed over more than three decades, since its discovery in 1986.

Hartley 2 Is Fading Fast

After considering the data from previous apparitions and accounting for the comet’s observing geometry (e.g., distance and viewing angle) in 2023, astronomers studying Hartley 2’s brightness noticed a clear and ongoing decline in its activity throughout the years. Their new paper reveals that the comet’s peak brightness is decreasing by about 0.59 ± 0.11 magnitudes each orbit — roughly a 42% drop every 6.5 years. With this information, they figure that during the 2017 apparition, Hartley 2 was technically no longer “hyperactive” by the community’s standards. The trend continued through 2023, marking over 30 years of steadily dimming.

This fading cannot be explained simply by changing geometry. Instead, the most likely explanation is volatile depletion — Hartley 2 is slowly running out of easily accessible ices. Other possibilities, such as fragmentation or a dust mantle forming on the surface, are less likely but still possible.

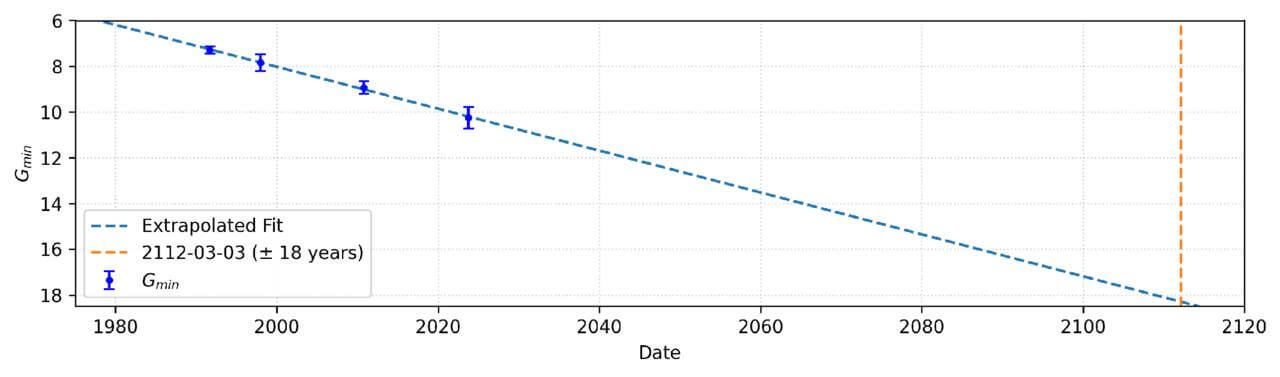

If Hartley 2’s brightness continues dimming each year at the same 42% rate, it could reach its “nuclear magnitude” — appearing essentially inactive —during its expected 2112 apparition. More realistically, the decline will level off as the remaining active patches become harder to deplete, meaning the comet may linger in a weakly active state much longer.

Figure 4 from Graykowski et al. 2025: Measurements of the minimum magnitude (G) of Hartley 2 associated with each apparition. This plot shows the decline in brightness as the magnitude as increaed over time, setting this comet on a course to become inactive by 2112 at the earliest.

Why Your Observations Matter

Cometary evolution is usually difficult to measure directly. Changes happen slowly, often over many decades or centuries. Hartley 2 is now one of the rare examples where we can watch a comet’s activity decline in real time, orbit after orbit, largely thanks to citizen astronomers and a serendipitously short orbital period.

This result was possible only because of the persistence and coordination of observers around the world. The new study highlights how citizen astronomers can collectively produce long-term, high-precision datasets that rival professional campaigns. In total, Unistellar Network observers obtained 64 observations from 59 different telescopes, and the AFA community obtained 147 datasets from 45 different telescopes for this study. These are the kinds of contributions that make this work possible.

Hartley 2 may be fading — but thanks to you, its story is becoming clearer than ever. Even though the Unistellar Network is done observing this “hyperactive” visitor, you can still make observations of many other interesting comets through our Cometary Activity program.